In Waterfront Hearings, Accounts of a Union’s Kickbacks and a Mafia Tie

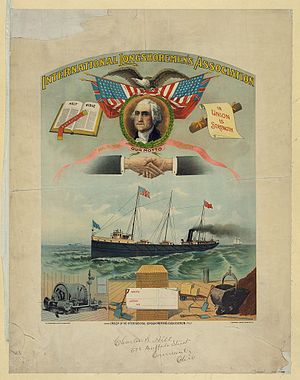

Image via Wikipedia Edward Aulisi was a dockworker — at least in theory. According to law enforcement officials, Mr. Aulisi, whose father led a longshoremen’s union local, knew of the local’s kickback payments to organized crime, and he was in contact with a Mafia captain who was a fugitive from justice.

Image via Wikipedia Edward Aulisi was a dockworker — at least in theory. According to law enforcement officials, Mr. Aulisi, whose father led a longshoremen’s union local, knew of the local’s kickback payments to organized crime, and he was in contact with a Mafia captain who was a fugitive from justice. And, they say, despite collecting about $100,000 a year in pay, Mr. Aulisi rarely, if ever, showed up for his job on the waterfront in Elizabeth, N.J.

This account of Mr. Aulisi’s career was made public on Thursday at the first in a series of hearings being held by the Waterfront Commission of New York Harbor, whose officials say they will expose favoritism, no-show jobs and organized-crime involvement on the docks.

The port’s thousands of dockworkers and the 64 freight-handling, or stevedoring, companies that employ them all need commission licenses to operate, and after years of lax oversight, the commission has made its background checks and licensing requirements more robust.

The commission was rocked by scandals of its own before new management took over, and the hearings in Lower Manhattan are meant, in part, to demonstrate that the need for its policing functions remains. A powerful Democratic state senator in New Jersey, Raymond Lesniak, has called for elimination of the commission, a position shared by some officials of the International Longshoremen’s Association.

On Thursday, the commission focused on Mr. Aulisi and longshoremen’s Local 1235, which was led for a few years by his father, Vincent. Edward Aulisi was called as a witness to answer the allegations, none of which have resulted in criminal charges, and in response to each question, he invoked his Fifth Amendment right against self-incrimination.

The commission produced records for two days in September 2009 when Mr. Aulisi was signed in — by somebody — at the waterfront and was paid for working 10-hour shifts, including overtime. But Vincent King, a detective with the commission’s police force, testified that on both days, he had Mr. Aulisi under surveillance, and “he was in fact at home at the time.”

Detective King showed photos he said he had taken on those days, one of Mr. Aulisi holding a spatula at a grill, another of him driving a riding lawnmower.

Detective King said he interviewed two people who were supposed to have worked with Mr. Aulisi tracking the movement of shipping containers for one of the waterfront companies, APM Terminals. One said he had not seen Mr. Aulisi in two years; the other said he had worked hours in Mr. Aulisi’s place several times.

Commission officials played a recording of what they said was a 2007 phone call from Mr. Aulisi to Michael Coppola, a captain in the Genovese crime family in hiding for more than a decade because he was a suspect in a murder case. The two men spoke using code, translated by Joseph Longo, another commission detective: “Christmases” meant kickback payments, for example, and “shingle” meant lawyer.

On the recording, the man said to be Mr. Aulisi updated the other man on news — a subpoena served to a Genovese associate, a loan shark customer falling short on a payment — and mentioned that the “Christmases” had doubled in a few years.

In 2007, Milton Mollen, a retired New York State judge hired by the longshoremen’s international to oversee ethical practices, expelled both Aulisis from the union. But APM continued to employ Edward Aulisi for two years, until the Waterfront Commission revoked his license.

Richard Carthas, senior director of terminal operations for APM, testified that he was aware during those two years that Mr. Aulisi had been stripped of his union membership and accused of working a no-show job.

Commissioner Ronald Goldstock asked, “Did you give instructions to your timekeepers, ‘Hey, let’s make sure Mr. Aulisi is actually showing up?’ ”

Mr. Carthas said he did not. He said APM took no disciplinary action against Mr. Aulisi because a trade group, the New York Shipping Association, advised that it would be difficult under the union’s contract.

The union’s contract requires that three “checkers,” Mr. Aulisi’s position, be hired for a given assignment like loading or unloading a ship, so that they can work in shifts around the clock. But, Mr. Carthas said, how the three divide up the work is entirely up to them.

“As long as that job was covered and there was somebody physically doing that job, that’s what our requirement was,” he said.

The commission contends that the contract produces constant overstaffing, so that people are routinely paid for hours they do not work, including significant overtime pay — a system that is ripe for abuse.

The commission was formed in the 1950s, in response to the same exposés that inspired the film “On the Waterfront.” Most top officials, including its two commissioners, were replaced in 2008 and 2009, after a series of scandals.

http://www.nytimes.com/2010/10/15/nyregion/15waterfront.html

0 comments:

Post a Comment