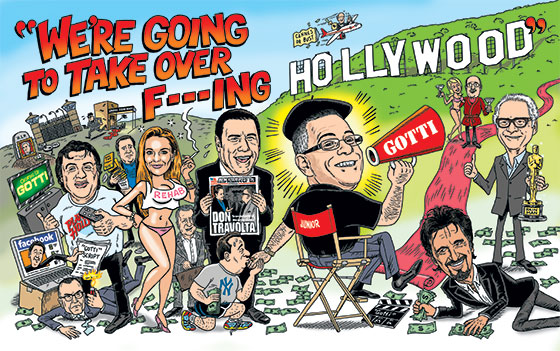

John Gotti Jr is trying to take over Hollywood

The start of it all, the unmoved mover, was John Gotti, legendary head of the Gambino crime family, a snarling, bloodthirsty, charismatic monster tightly encased in a shiny Brioni suit. After he had previous Gambino boss Paul Castellano murdered outside Sparks Steak House in 1985, a stunning piece of Mafia theater replete with costumed hit men and walkie-talkies, Gotti thoroughly dominated his era, orchestrating dozens of murders—and making it impossible, because of his fame and flamboyance and pure viciousness, for anyone to be a mobster in quite that way again. “You’ll never see another one like me,” he once said.

So what is the son and chosen heir of such a man to do? After five criminal prosecutions and nine years in prison, after millions of dollars of asset seizures, with the world he knew as a child no longer in existence, with the Ravenite social club where his father ordered hits now a trendy Nolita shoe store, what, exactly, is his patrimony?

I was talking to John “Junior” Gotti about these questions, his father, and his way forward over espressos one recent afternoon. There were pale echoes of the former Gotti life. We were at Da Mikele, a Tribeca restaurant that is owned in part by his lawyer and friend Tony D’Aiuto; Vinny the bartender was Gotti’s sometime driver.

John Gotti is 48 years old, wide-bodied and narrow-eyed, with two-tone hair: gray creeping up the sides, still black on top. He was dressed in a black-and-white cabana shirt, black jeans, black shoes, a hipster but for the strapping build.

Junior is a chip off the old block—but only a chip. “He was handsome, he was charismatic,” Junior said, with something like awe of his father’s Mephistophelian glamour. “Not a hypocritical bone in his body. He told you what he was. He made a choice. I was proud to be around him, proud to be under him. He acted … like a man.”

But when Junior faced twenty years in prison, his outlook changed. He reflected on the wisdom of following in those giant footsteps. He realized that he wasn’t his father, couldn’t be. And in 1999, in a visit at the supermax prison where Gotti Sr. was serving life without parole, the son told the father he wanted to take a plea, serve his time, and leave the Mafia.

The decision still troubles him. “Was walking away the right thing to do or the wrong thing to do? Am I making my wife and children happy by what I’m doing? Did I hurt my father? Was he disappointed in me?” Junior asked. He paused, as if deciding whether to answer his own question.

“I did feel like he was disappointed. I still do. To be honest with you, I have to wrestle with that every day.”

You can check out of the Mafia—but you can never really leave. After the Don died, in 2002, John Gotti Junior no longer had a father or a Mafia empire—but what he did have was a story. He started by writing a book based on his massive archive of documents and transcripts, some conveniently provided by FBI wiretaps—it grew to a thousand pages but never really took off. Then Gotti heard that movie producers were going to try to muscle in on his territory, make a movie about his father. That’s when he realized he had to make that movie himself. It made perfect sense—Hollywood has always been Mafia heaven—and how different were the mob and Hollywood, after all? Both in the Mafia and in the movies, a bloodthirsty boss could be a man of honor.

“It’s a fascinating story,” Gotti says, as if pitching the picture to me. “It’s an opportunity to say, ‘Look at the street life.’ ” He pierced the air with a thick finger. “People don’t see the pain. They don’t see my mother, 23 years without my father. They don’t see my wife without me. They don’t see houses and buildings that were taken from me. Businesses that were taken from me. They don’t see the price that we had to pay, the tolls that were taken on my children. They don’t see any of it. I think the movie will help me … because it’s an explanation.”

Whereas his father had wanted to rule, Junior wants to be understood, and also wants the catharsis of telling his story. Plus there was that other thing both Hollywood and the Mafia understand: money. Junior was nearly broke, largely from paying his lawyers. The story represented his inheritance.

Gottis do things in their way, and selling the movie was no different. Junior didn’t hire an agent. He likes to deal with people he knows, people he trusts. So he put out the word through his lawyer, D’Aiuto, and also through an ex-brother-in-law in the pizza business in L.A.

It didn’t take long to discover that even in death, John Gotti had clout. As if by magnetic pull, interested parties started knocking on Gotti’s door. There were producers looking to start a new chapter, stars hoping for one last star turn. In a way, they needed Gotti more than Gotti needed them.

The first star to see the possibilities inherent in playing John Gotti was, perhaps not surprisingly, Sylvester Stallone. Stallone is only half-Italian, but he made his reputation playing tough guys with vowels at the ends of their names who had to fight for respect—and at this point in his career, he felt that “he wanted to be taken seriously as an actor,” explained a confidant. Stallone, still dark-haired at 66, with trademark fish-hooked lip and slurred speech, told Gotti he would direct the film himself, as he’d done with his Rambo and Rocky franchises. In fact, Stallone wanted near-total control—but he wasn’t offering much money. It was an offer that was easy for Gotti to refuse.

Gottis like loyalty and control. They lead; they don’t follow. They need lieutenants. And that is where Marc Fiore came in. On one level, Fiore made an unlikely producer for a movie about the greatest mafioso of his era. A portly former small-time Wall Street operator who’d been in jail briefly for securities fraud, he had no experience in Hollywood. His office is in Manalapan, New Jersey, 30 minutes from the Jersey shore.

But, ignorant as he may have been of the ways of the movie business, he had cultural knowledge that was even more important. Both Junior and Fiore came from close-knit Italian families—Fiore is from Bensonhurst, Gotti from Howard Beach. And Fiore was steeped in the myths and glamour of the Mafia. “Everybody in the neighborhood knew somebody who was connected,” Fiore told me. As for John Gotti Sr., he was “an icon,” said Fiore. “For a guy like myself, I’m the perfect audience.” Even his short stint behind bars helped him relate—though one member of Junior’s crew cracked that “he’d done time in a camp for taking money from old ladies.”

Fiore was understandably nervous about having a sit-down with a man named John Gotti, even though the meeting took place in the safe environs of a lawyer’s office in Long Island, near Gotti’s home. But Gotti settled him down. “I’ll tell you a story,” he said. “This will amuse you.” And then he unspooled tales of his father, pausing for effect, playing different parts, clearly relishing the performance.

Gotti remembered walking into Lewisburg prison as a 7-year-old child to visit his father, looking at a guard with a shotgun on a high wall, and jumping into his mother’s arms because he was so afraid. There was the time his father berated him after Junior told him that he planned to be a cop for Halloween. Then he told Fiore about his father on his deathbed. “He’s lying in bed in prison, 130 pounds, ravaged by cancer,” Gotti said. “My father had lost the power of speech.” A priest walked in to administer last rites, a final chance to renounce his sins. His father shook his head. When the priest didn’t understand, John Gotti made a gesture with his hand as if shooing away a fly. “He wasn’t going to turn around and say, ‘I’m so sorry for being me.’ Right or wrong. The honor that this man carried with him!”

By the time Gotti finished, Fiore was ready to deal. But there were two more questions Gotti wanted answered.

“How interested are you in accuracy?” he asked.

“I want to do what you want to do,” Fiore said.

Gotti insisted the movie be at least 70 percent factual—plus script approval.

“I’ll give that to you in writing,” said Fiore.

“And he did; we have that number in the contract,” Gotti told me. “And no one else in Hollywood would give me that.”

The other question was: How much? And to that, Fiore’s answer was more than satisfactory—he would pay Junior a seven-figure fee—more than twice what Stallone had been willing to put up.

For Fiore, it was worth the price. With the Gotti property, he felt he had his “chess piece in Hollywood.” As he later said to Gotti, using language that the elder John Gotti might have approved of, “We’re going to take over fucking Hollywood.”

This turned out not to be quite so easy. With the help of his Hollywood muscle—that would be Stuttering John, Howard Stern’s sidekick, whom Fiore had once helped to produce a straight-to-DVD movie, his only credit—he managed to wangle a few meetings. “They were favors, and you could tell,” said Fiore. “As soon as you’re sitting down, you’re getting up.”

The meetings tended to last just long enough to deliver the wisdom of the moment: Nobody wants to see mob movies anymore. Fiore didn’t buy that. “I think it was me,” Fiore told me. “I was a nobody.” And indeed, this was a big part of the problem. Fiore’s presentation was outlandish. He had the wrong accent and wore the wrong clothes—a suit that barely contained him, with garish cuff links. “He was a shocking amateur. He would truly never know what he was talking about,” said an industry player. Which was certainly true when he was talking about Hollywood—at the time he met Gotti, Fiore hadn’t even seen The Godfather.

But Fiore did have one impressive attribute, and that was money. At a Yankees game, he’d met Fay Devlin, an Irish immigrant with an adventurous streak. At age 24, Devlin had founded Eurotech, a Manhattan-based construction company with more than $80 million a year in sales. Devlin was, if possible, even less experienced than Fiore in the movie business, a fact for which he doesn’t apologize. “Of course we are outsiders; so is everybody at some stage,” he told me. “You have to listen to your gut.” So Devlin became a 50-50 partner in Fiore Films and its principal funder. “Holy shit,” he said at the prospect of the Gotti rights. “This is a no-brainer.”

Fiore already had a screenwriter lined up. His meeting with Gotti had been brokered by a longtime character actor and sometime screenwriter named Leo Rossi, who’d heard about the Gotti rights through the ex-brother-in-law in the pizza business. Rossi moved from Los Angeles to Long Island and spent five months interviewing Gotti, taking notes since Gotti wouldn’t permit a tape recorder. “I’ve been taped too much in my life,” Gotti told me.

“The movie is seen through my eyes,” Gotti told me, and the treatment is built around his unusual boyhood and his midlife career change. For Junior, the Bergin Hunt and Fish Club, his father’s headquarters, was a fun place to hang out. His uncles were there—his father’s brothers worked for him—and everyone made sure to treat the boss’s son right. “I loved going to the club on Saturdays,” Junior told me. “I loved the way everybody treated me. Taking me to the toy store. Giving me five bucks. People were talking about food and barbecuing and sports and boxing and gambling, betting on the game tomorrow.” It was only natural that a son in thrall to a father would graduate from weekend ball-breaking into the father’s business—which happened to be loan-sharking, extortion, and murder.

But Junior wasn’t his father, a man who grew up “dirt poor,” as Junior described it, and had never considered any career but gangster. He was the boss’s son but also a suburban kid. Occasionally, he sauntered into the social club with a Walkman playing in his ears—an entitled, Gen-X version of a gangster.

The movie’s climactic scene takes place over a formal conference table at Marion prison in Illinois. It was 1999, and Junior had been charged with extortion and racketeering and faced a long sentence. The government was offering a plea, and he wanted to take it and retire from the mob. “I’d follow you over a cliff,” he told his father. But he wanted his father’s blessing: The code word for it was closure.

“That word is not in my vocabulary,” the father told his son. “That’s [for] overeducated, underintelligent motherfuckers … that word, ‘closure.’ ”

Ultimately, Junior chose his children over his father. He took the plea, served seven years, a good portion of it in solitary, and never saw his father again.

Great material. For Fiore, the challenge was getting producers and agents to see past him—the 325-pound, Brooklyn-accented salesperson (“delusional,” one insider called him) to the property itself. Which wasn’t easy. His other emissary to Hollywood besides Stuttering John was a 77-year-old gadfly and publicity hound named Marty Ingels, who looks like Captain Kangaroo and has a once-famous wife, Shirley Jones, late of the Partridge Family.

“We’re looking for some stars,” Fiore told Ingels. What about John Travolta? Travolta was the perfect man to play the Don. A Jersey boy and son of a tire salesman, whose breakout movie, Saturday Night Fever, was set in the same Brooklyn provinces where John Gotti had made his bones. And so Ingels mounted a yearlong campaign, a blend of agitprop and schmaltz, to get Travolta’s attention. After Travolta’s son Benjamin was born, Ingels pretended the Old Testament name meant the boy was Jewish. He inundated the baby—Benny or Benji, he called him—with e-mails signed by his Jewish uncle, Uncle M, and offered advice on the High Holidays. Amazingly, the campaign worked—he got Travolta to read the script. Travolta was already rich, even by movie-star standards—he owns five planes, including a wide-bodied Boeing 707, which he parks in a hangar connected to his house. Still, he wasn’t the leading man he’d once been. He hasn’t done anything with real heft since The Thin Red Line, in 1998. But John Gotti—that was a role for a real movie star. “What a character to approach and understand,” Travolta would later say. “He’s filled with incredible dichotomies. I like the glamour, the humor. There was mystery about what he was up to. I like playing that, too.”

Travolta agreed to meet for dinner—for a price, which was a deposit of close to a million dollars. That dinner was followed by another, to meet Junior, at Amici, a favorite Travolta restaurant in Brentwood—Travolta took the precaution of closing the restaurant for the evening. Outside, paparazzi tried to break down the door. Inside, a dozen people crowded around a long table, looking on as Travolta interrogated Gotti about his father’s habits. “What would he have ordered for dinner?” he asked.

The two bonded over a tragedy. “You want to know what conversation really got me to seriously like John Travolta?” Gotti said. “He asked me a question: How did your mom and dad deal with the death of your brother?” In 1980, Frank Gotti, then 12 years old, was broadsided by a neighbor after darting into the street on a motorbike. “I told him that for twenty years, she was really almost immobilized. And still, to this day, she has good and bad days.”

Travolta had lost a son—Jett Travolta died in 2009 after a seizure. “Travolta looked at me, and he got all teary-eyed and cried. And he said, ‘You know, I must have watched Barney 5,000 times with my son. I’d give my life to watch it 5,001 times.’ ”

“It got a little emotional for the both of us,” Gotti told me, “and I saw the heart in this man, and I said, ‘You know what? He’s the right guy for this movie.’ ”

Travolta signed—for a reported $10 million.

As luck would have it, Victoria Gotti, Junior’s sister, who’d been the first to monetize the Gotti name with her own reality show, Growing Up Gotti, happened to be friends with another star in need of a break—fellow Long Islander Lindsay Lohan. And Lohan, after the DUIs and jewelry arrests and even a stint in jail, was eager for a role in the movie. Victoria called Fiore on Lohan’s behalf: “Is there anything you can do?” she asked.

“I’d love to have Lindsay in my movie,” he said. Sold!

The final piece of the puzzle was a director. Most agents wouldn’t take Fiore’s calls, but luckily Rossi happened to know someone who knew the brother of Nick Cassavetes. Cassavetes was a Hollywood name brand, having directed Alpha Dog, John Q, My Sister’s Keeper. But to Fiore, those were mere details. What made him happy, he told me, was that Cassavetes “was a real director, with a real agency behind him”—ICM. “Having Cassavetes was a real step for us.”

Travolta quickly slipped into his new role, making the rounds of the Gotti clan, doing research and paying respect. He visited Gotti’s mother at the modest Howard Beach house with the trim lawn and white clapboard siding, its backyard abutting the neighbor who’d accidentally killed her son. (John’s mother Victoria, as tough as her husband, had attacked the driver with a baseball bat and landed him in the hospital. A few months later, he disappeared. (“Did my father kill him?” Gotti said. “Yeah, probably.”)

Mrs. Gotti put out a hearty Italian spread of mozzarella and meats and then led the star up the stairs to her husband’s closet. She’d preserved his clothes just as he’d left them—the $2,000 Armani suits and hand-painted ties, along with dozens of Bruno Magli shoes. In return for this privileged glimpse, Travolta shared movie-star anecdotes, like the time he met Sophia Loren. It was all one big happy Hollywood-Mafia family.

Until it wasn’t. Hollywood guys like to think of themselves as tough guys, too. And Cassavetes, a scion to Hollywood royalty (he’s the son of Gena Rowlands and John Cassavetes), is more macho than most, with tattoos on his knuckles and a taste for high-stakes poker. In classic Hollywood fashion, he said the Rossi script was “brilliant,” while working on his own script. In Cassavetes’s version, John Gotti wore a cowboy hat and whacked people with baseball bats. “Jason [in Friday the 13th] meets GoodFellas,” Gotti explained. “Maybe it would put asses in the seats. But was it something we could live with?”

Fiore’s hands were tied—he couldn’t defy Junior. “We don’t have a choice,” he told Cassavetes. “We have to make his movie.” Cassavetes quit.

Fiore, by this time, however, had a few more Hollywood friends. He reached out to Cassavetes’s agent, Jeff Berg, the 65-year-old then–chairman and CEO of ICM who, like everyone else in town, jumped on the phone with him. They were the oddest of couples, the oafish outsider and the consummate insider. But they had one thing in common—they wanted this movie made. Berg’s agency was drifting, its movie side in particular. A star-driven hit put together by ICM could be a boost Berg needed. And besides, this movie came financed. Fiore claimed to have a fortune at his disposal, some $250 million from unnamed Middle Eastern investors, in addition to the development money from Devlin.

Berg was famous for his chilly style—his nickname is Iceberg—but the kind of cash Fiore promised produced a thaw. Berg quickly hooked Fiore up with an even more prestigious director in the ICM stable: Academy Award winner Barry Levinson. The director had been in the business for more than 40 years, making classics like Diner, Bugsy, and Rain Man, the 1988 film for which he won his Oscar. At 70, Levinson, too, was pushing against the clock.

Levinson, a man from the same generation as Gotti Sr., was captivated by the material. He loved the story about Senior’s Mafia mentor, Aniello Dellacroce, another brash, foul-mouthed killer. In 1985, Dellacroce, a rabid sports fan, was dying of cancer and confined to bed. Gotti had a satellite dish installed on his roof. Then Gotti crawled into bed with his mentor so they could watch sports together. “What an amazing sequence,” Levinson told me. “I didn’t want to do a mob movie, but this is completely outside what we know or anything we’ve seen in a gangster movie. That’s why I loooove the project.”

Fiore made Levinson a down payment of upwards of $500,000, a portion of which Levinson paid to screenwriter James Toback (Bugsy, among others), who put the scenes into script form. Talks were started with Ben Foster (X-Men: the Last Stand) to play Junior. Levinson reached out to his friend Al Pacino, 72, to play Dellacroce. Mob films are in Pacino’s blood—and of course the money was nice too. Fiore offered him $7 million for the supporting role.

“He overpaid like crazy,” said one source, though he understood. “Otherwise no one would listen to him.”

But to write checks, you need money in the bank, and Fiore Films had less than he’d let on. The team had already laid out as much $10 million of Devlin’s. Fiore needed to raise about $55 million to make the movie, a daunting sum, since the quarter of a billion hadn’t materialized.

Still, Fiore reminded himself, he was a Hollywood producer, and he did what he thought producers do, which is to go to Cannes to troll for foreign distributors—they thought they could make as much as $25 million. “We paid a fortune to go to Cannes,” Fiore told me. They flew in more than a dozen people—each first-class ticket cost $16,000. They paid for hotel rooms at $2,500 a night. ICM invited foreign buyers to a cocktail party at the Majestic Hotel—Salon Martha, with an entrance off the pool terrace. “Barry makes a nice speech. We are like, ‘Oh, this is unbelievable. This is great,’ ” recalled Fiore.

But Cannes was a disaster. Levinson talked up the movie to the press but was rethinking the cast as he went. He wasn’t interested in Lohan, he said, which Fiore heard about in an emotional 2 a.m. call from Lohan.

“It’s my fucking movie,” Fiore had taken to saying, and he released his own statement. “Lindsay Lohan is a talented and beautiful actress. She is in the film.”

At that point, Fiore and Levinson stopped speaking.

There was worse news out of Cannes. Fiore Films hadn’t closed any foreign sales. Fiore had been naïve. He didn’t know what he didn’t know. He needed a sales agent, and ICM hadn’t rounded one up in time for Cannes.

“There was lots of heat, but there was no one there to close the deals. For Marc to have arrived in Cannes with Barry Levinson and a cast in place and without an international sales agent was crazy,” said Dennis Davidson, the well-known publicity agent who’d been lined up by Berg to represent the film at Cannes. “I have no doubt that had they had a sales agent, they would have come out with a chunk of change.” (“We did exactly what we were asked to do,” an ICM spokesman said.)

By the fall of 2011, Fiore had severed the relationship with ICM. ICM claimed to have no regrets; it wasn’t only his limited Hollywood experience, or his foul mouth; Fiore couldn’t come up with the funds he said he had. “He had excuses, one story after another,” said an insider.

Fiore was humiliated. He felt double-crossed—he didn’t know any longer who his friends were, what kind of plots were being hatched. “I was a pigeon,” he said.

Fiore was right to be paranoid. Because someone was trying to have him whacked. In November 2011, with the movie moribund, John Gotti received a phone call at home. Levinson’s agent at ICM, John Burnham, was on the line, asking how long Gotti’s rights were tied up with Fiore. The clear message was that the movie still could get made—if Fiore could be eliminated.

Gotti knew his way around assassination plots. He didn’t bat an eye at this proposition. “It’s business. It’s business,” he later explained to me. “I respect that.”

Fiore’s Hollywood career was hanging by a thread. But then, in a plot twist from an entirely different kind of movie, a fairy godfather dropped out of the clear blue sky. Ted Field, 60, is a Hollywood legend—heir to the Marshall Field fortune, former race-car driver, famed playboy, music impresario, and producer of more than 50 movies. Field knew just what to say to Fiore and Devlin, who flew to meet him the day that Gotti received the call from Burnham. “I can’t believe you guys got this far on your own,” he told them. “You should’ve had more respect from the get-go.”

Fiore had longed to hear just those words. “That was a feather in my cap as a businessman,” said Fiore. “To hear that from Ted, not just because he’s from Hollywood but also because he’s a billionaire.”

And then, too, Fiore had been changed by his adventures—he was eager to let someone else run the show. “Marc is allowing me to navigate the Hollywood system,” Field explained diplomatically. A good thing, since Levinson won’t even respond to Fiore’s e-mails. The project is starting over again with a new screenwriter, Lem Dobbs (coming off Steven Soderbergh’s Haywire), hand-picked by Field and, this time, a foreign sales agent, IM Global. And Fiore is bragging that he’s got a line on a new $250 million, though Field will believe it when he sees it.

One day last month, Fiore greeted me in his office suite in Manalapan. The offices were empty—no one works there except Fiore. Fiore had hung movie posters on the wall, including Saturday Night Fever with Travolta in the famous white hip-hugging jeans, and a framed front page of the Post: don travolta, it said. He also had a poster of the Gotti movie, though Lohan’s name was covered by a pink Post-it—and Joe Pesci’s was blacked out. He’d been cast as Senior’s best friend but is suing after Levinson changed his part.

Fiore led me down the hall, stopping off in a storeroom to show me stacks of DVDs from the Stuttering John movie—the distributor said they’d sold zero, though Fiore disputed that. He’d purchased two. We moved to his corner office, with a view of the parking lot. Fiore was wearing a New York Yankees T-shirt and dark gym shorts. “It’s Hollywood,” he said with a shrug—in Hollywood, he’d learned, the most powerful people dress casually. He folded his arms on his glass-topped desk. “Quite frankly, our goal is to build an empire,” he told me. Then he confided a dream, the one that had sustained him through all the setbacks. In the dream, he imagined himself onstage at the Academy Awards. He’d already written his acceptance speech, he told me. “It might be the best speech ever at the Academy Awards,” he said. He planned to settle some scores. “I might expose some people. I’d be afraid of me,” he said and laughed.

It was late afternoon at Da Mikele. The evening crowd hadn’t arrived yet, and Gotti had the run of the place. We’d covered a bunch of subjects, but as our time ended, conversation circled back to the one that engaged him most: the fork in the road. “I was on that path”—to be a mobster like his father—“and I had to go in a different direction. I had to change my whole entire life,” he told me. “Like my whole life is a blooper.” And so he’d changed. “My friends are mostly doctors and lawyers today,” Gotti said, sounding surprised. “That’s who I socialize with: professional people, along with my wife, my children.” For Gotti, the life of the gangster now exists mainly in the movie he hopes to make. And so, as the espresso disappeared, Gotti got to storyboarding again. “A lot of writers miss the wedding scene.” The Godfather, of course, begins with a wedding, but in Junior’s film, called Gotti: In the Shadow of the Father, the wedding is Junior’s. It took place at the Helmsley Palace in 1992, and in honor of the day, Leona Helmsley draped a twenty-foot Italian flag outside the hotel. Gotti’s best man was his first soldier, who was later murdered. Every New York family had its own table, each mobster dressed in a tux. There was lobster and Cristal. Gangsters handed Junior envelopes of cash—a haul of $348,000—and then lined up at Senior’s table to pay homage, all the while plotting to settle scores. “That scene will be in there,” said Gotti confidently. “We want something Godfather-esque.”

Fiore has finally seen the movie.

http://nymag.com/news/features/john-gotti-jr-2012-9/

0 comments:

Post a Comment