Head of Rhode Island state police spent six years undercover taking down the Patriarca crime family

“Steve Foley” was living a lie -– one that would last six long and dangerous years.

It

all started on Sept. 27, 1994, outside a Providence, R.I., courthouse,

when he recognized a hit man for the most powerful crime family in New

England.

He walked up, said hello and told the killer he had remembered him from prison.

But

“Foley” wasn’t the profane and menacing long-haired bookie and drug

dealer he professed to be. He was Steven O’Donnell, an undercover state

police officer trying to get inside one of the Mafia’s most feared

families. He knew the job was dangerous and that the slightest mistake

was likely to get him killed.

“Everybody

has fear,” he says now of the stretch in the mid-1990s that he spent

working inside the Patriarca Mafia family that ran New England, worried

that he’d be exposed or that his wife and family would be at risk. “…

Only to stay on top of your game, you have to be in full control of that

fear.”

In part because of that

healthy sense of apprehension, O’Donnell’s dangerous assignment to

infiltrate the powerful crime family founded by Raymond Patriarca Sr. in

the 1950s had a happy ending for everyone but the mobsters. His

testimony was instrumental in convicting “hundreds” of criminals and

putting them behind bars.

It also served as an

effective, if unlikely, crash course that prepared him for his current

position: head of the Rhode Island State Police, the top public safety

job in the state.

“Because of (my)

undercover work, I am non-reactionary,” said the 53-year-old O’Donnell,

in his first detailed interview about the case. “… You can tell me

something bad happened and I’m not going to react to it. I’ll get all

the facts first.”

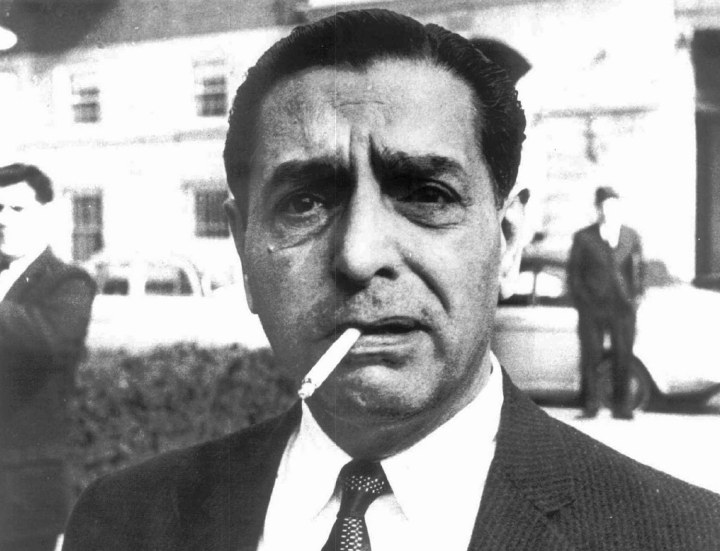

It took a guy who grew up around the mob to take down the mob.

O’Donnell

is from Providence, and as a boy lived across the street from a woman

who was dating “a made member of the Patriarca crime family,” a feared

outfit run by “one of the most powerful dons in the history of America,

never mind New England,” he says.

He was fascinated by the crooks he encountered, but they also fueled a sense of moral indignation.

“I was always kinda frustrated that they can do what they do with … impunity,” he said.

That

led O’Donnell to a career in law enforcement, first as a guard at Rhode

Island’s Adult Correctional Institute, starting in 1983, and later as a

state police officer.

Prison is a lot different inside than what people perceive on the outside.

O’Donnell, who guarded

the “wise guys” -- or mobsters – in the prison’s maximum security wing,

says that monitoring prisoners was the equivalent of earning a graduate

degree.

“You can't beat the

experience that you have to talk to people, you have to listen to 'em. …

Prison is a lot different inside than what people perceive on the

outside,” he said.

It was while

working in the prison in the ‘80s that he first encountered Harold

Tillinghast, a hit man doing time for murder who was in charge of fixing

TV sets and grilling hot dogs for his fellow prisoners.

Guard

and inmate had little interaction at that time, but a chance encounter

with Tillinghast years later,when O’Donnell was working as a Rhode

Island trooper, dramatically changed his career’s trajectory.

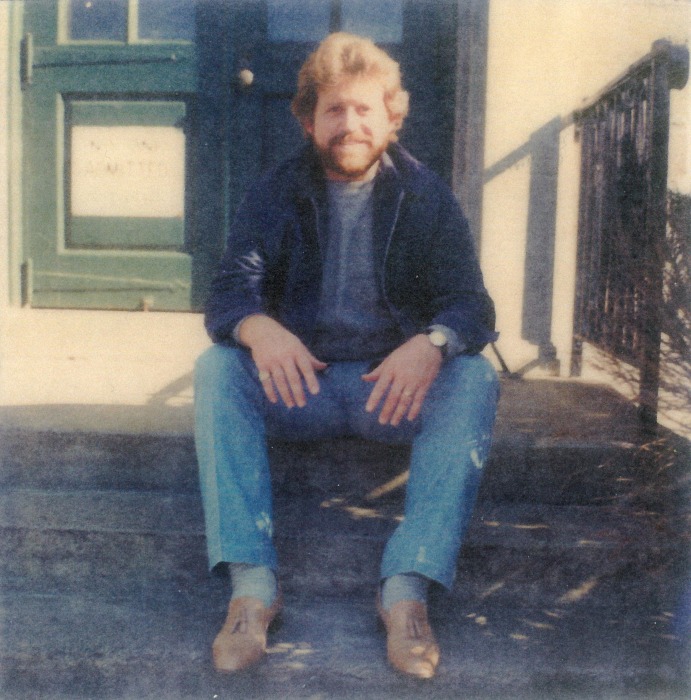

O’Donnell

was assigned at the time to the agency’s Intelligence Unit, which had

made tackling organized crime its top priority. It wasn’t easy, but he

persuaded officials at the regimented agency to let him grow a beard and

wear his hair long so that he could more easily mingle with the crooks

he was targeting. He also had an array of false documentation, including

driver’s licenses and student IDs, that he carried with him, just in

case an opportunity presented itself.

That moment arrived on Sept. 27, 1994, when he recognized Tillinghast outside a Providence courthouse.

After

sizing up the situation for about five seconds, he introduced himself

to Tillinghast as Steve Foley and said they had done time together in

prison. Tillinghast, who was out on probation, didn’t remember

O’Donnell, but the undercover cop’s story won him over.

“I

convinced him that I was an inmate, and I knew the walk, I knew the

talk,” O’Donnell said. “… I knew what he did for work, what block means,

where you work, what, how you eat.”

O’Donnell

built a friendship with Tillinghast over the following months before

playing his next card, telling the mobster that he was a bookie who

needed to “lay off” some bets that had him financially exposed. He also

said he was looking to pay for “protection” to the local mob to avoid

stepping on any toes, but didn’t know who to talk to.

Tillinghast

was happy to help and introduced him to another criminal, Joseph Lema,

an oddsmaker who also collected a “fee” so that other local crooks

wouldn’t bother his new friend. When O’Donnell received threats anyway,

Lema picked up the phone and called Gerald Tillinghast, Harold’s

brother.

Gerry Tillinghast, the

muscle behind one of the Patriarca family’s crews, was still in prison

for murder – a killing that he and his brother were convicted of

carrying out. But he was continuing to run his gang’s rackets from

behind bars. Tillinghast had a simple response for Lema: Tell Steve to

tell the other gang, “Hey, he’s mine. Leave him alone.”

What the two men didn’t know is that the phone call, along with many others, was being recorded. NBC News has obtained audio of one of the phone calls, the first time it has been made public.

Posing as Steve Foley

was nerve-wracking, O’Donnell recalls, not just because he had to avoid

tipping off the mobsters. He was always worried that he would run into

someone who would recognize him as a cop and inadvertently blow his

cover.

“That happened a lot,

where I’d see people that I clearly recognized, that they know I’m a

state trooper,” he said. “….Rhode Island’s not a big place.”'

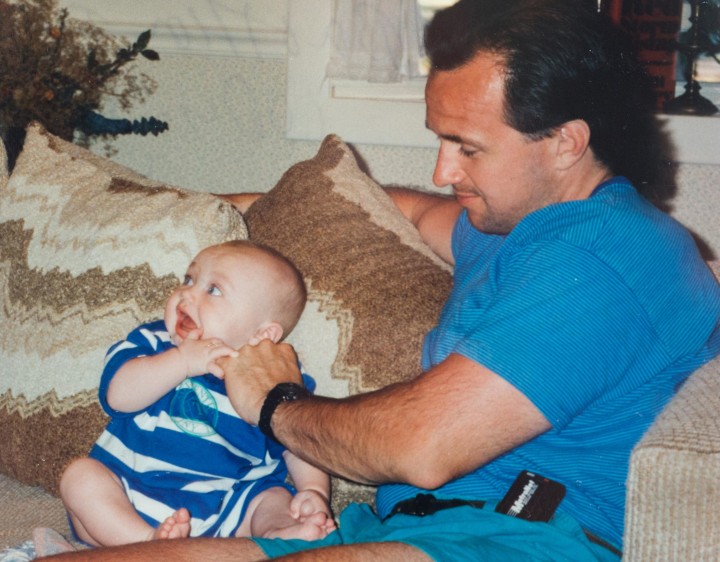

He

also feared what might happen to his wife, Holly, and their three young

sons -- Conor, Cody and Brady – if he was exposed. He says he didn’t

tell his wife too much about what he was doing, but she had some idea of

what he was doing and supported him.

“I mean, obviously she

knows how I look, she sees me comin' and goin' in different cars and I

talk to her about it as best I can,” he said. “(But) she doesn't live in

the world that I live in, and I don't want her to. “

Despite

such hazards, O’Donnell continued to build a massive dossier of

evidence against the crooks, until authorities finally began to reel

them in, starting in 1990.

By the time he cut his

hair and returned to uniform in 1996, O’Donnell’s testimony had been

instrumental in putting hundreds of suspected mobsters behind bars and

led to the seizure of vehicles, drugs and hundreds of thousands of

dollars.

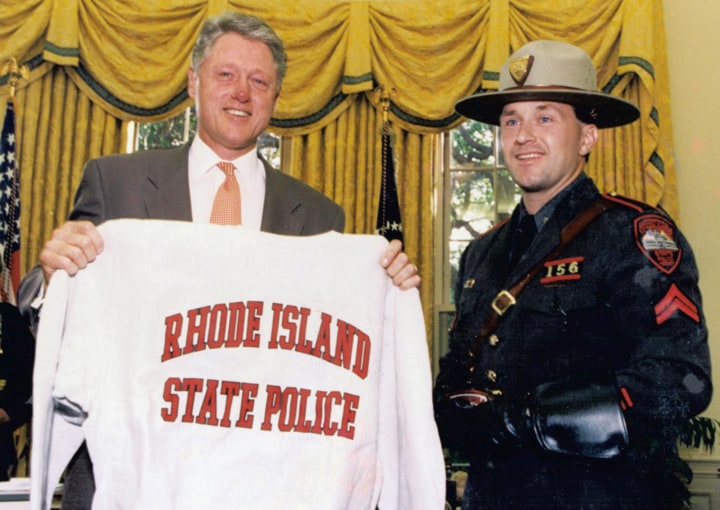

The busts, which gutted

the Patriarca family, earned O’Donnell honors and accolades that

extended to the White House, where he met former President Bill Clinton

and regaled him with stories of his days playing lacrosse in college.

His moxie even earned the respect of some of the mob men he took down.

In

a rare interview from his lawyer's Rhode Island office, where he is

serving probation, Gerry Tillinghast told NBC News that he bears no ill

will toward his old adversary.

“Lemme

say this,” he said, “my personal opinion is law enforcement, their job

is to take people that commit crimes -- no matter what level -- off the

street. That's their job. A criminal, no matter what level, his job is

then not to let that happen.”

As for O’Donnell’s ruse

that sent he and his brother to jail, Tillinghast said, “He did it

pretty good. I gotta give it to him, even though I hate to say it.”

O’Donnell says there

are no hard feelings on his part, either. O’Donnell said law enforcement

“respect(s) them in the sense that when they get arrested, it's not

personal. It's part of the system that we're in. I think it's important

it happens that way.”

There are

few signs of O’Donnell’s long undercover assignment visible in the

wood-paneled office reserved for the colonel and superintendent of the

Rhode Island State Police, where he oversees more than 600 state

troopers and civilian employees.

The

fake IDs and wiretap cassettes have long-since been filed away. His

low-slung L-shaped desk is neatly stacked with paperwork. There are

pictures of his kids playing lacrosse on a team he coached to a state

championship. There are no photos of the colonel during his days as a

long-haired, swearing, bookmaking, undercover detective in the mob.

For

those who know his story, there are a few mementos that hold clues to

his former occupation: There are pictures of him with President Clinton.

And there’s a photo of O’Donnell posing with legendary FBI undercover

detective Joe Pistone, aka “Donnie Brasco,” who infiltrated the Bonanno

and Colombo Mafia families in the late ‘70s and early ‘80s.

The most obvious reference may be the fake white street sign near the left corner of the room. It reads “Mafia Parking Only.”

http://www.nbcnews.com/news/investigations/taking-down-mob-undercover-cops-six-years-risky-business-n41556

0 comments:

Post a Comment