Notorious Rochester hit man dies in prison

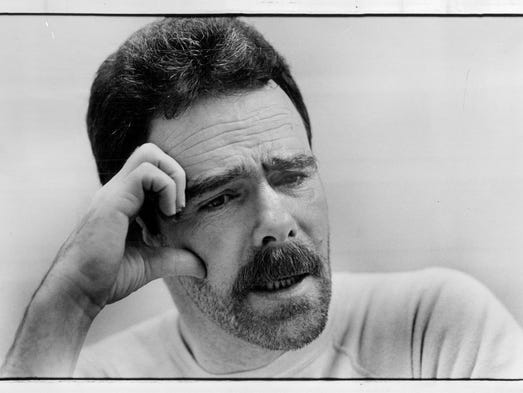

Joseph "Mad Dog" Sullivan, a hit man whose very nickname spoke of his violent tendencies, died in a New York prison Friday at the age of 78.

While Sullivan made his reputation as a contract hit man in New York City, he was responsible for a notorious Rochester mob killing — the fatal shooting in December 1981 of John Fiorino at the Blue Gardenia restaurant — that led to his imprisonment. He was serving three life sentences when he died.

Sullivan also once escaped from the maximum-security Attica Correctional Facility in Wyoming County, the only inmate to ever do so.

How many homicides Sullivan committed during his life is an unanswered question, though police and prosecutors have suspected that he was responsible for more than 20. As a 1982 Democrat and Chronicle article noted, "A trail of death has seemed to follow Joseph John Sullivan."

His victims, the article said, "have died a variety of ways: slashings, stabbings, shootings."

There is no question, however, that Sullivan fatally shot Fiorino at the Irondequoit restaurant in 1981. Two local mobsters, Thomas Taylor and Thomas Torpey, hired Sullivan for the killing.

Taylor and Sullivan had earlier served time together in the Attica prison.

Fiorino was a Teamsters vice president ensconced in mob circles. There are varying stories as to the motivation for his murder — either a belief that Fiorino was a snitch, a fear that he could bring mob factions together and take control, or retribution for his efforts to elicit payments from local organized crime figures.

In the late 1970s, Rochester witnessed an organized crime war, complete with bombings and shootings, between what were known as the A Team and B Team. Taylor and Torpey were bodyguards for the charismatic and popular Salvatore "Sammy G" Gingello, a mob leader who was killed in a car bombing in April 1978.

Joseph "Mad Dog" Sullivan, a hired hit man responsible for a notorious Rochester mob hit, has died in prison. Sullivan, 78, was serving three life sentences.

Taylor and Torpey then tried to build their own controlling mob unit, which police and the press labeled the C Team. According to retired FBI Special Agent William Dillon, an investigator during the mob era, Fiorino wanted to pull the battling contingents together.

"He was the one who was attempting to be the peacemaker," Dillon said. " ... He felt a kinship with Tommy Taylor and Tommy Torpey. He was the one who apparently was the most accessible to the C Team and the one that, we felt from our information at the time, who was most feared by the C team because he was the one who could be most like Sammy (Gingello)."

Fiorino also once clashed with Torpey after Torpey refused to make payments to higher-ups in mob circles from a gambling operation that Torpey ran.

Once Taylor and Torpey hired Sullivan, bringing him from his hometown of New York City for the killing, they faced a problem: Making sure Sullivan knew exactly who Fiorino was. They enlisted a minor player in mob circles, Louis DiGiulio, to accompany Sullivan and ID Fiorino.

'A stone-cold contract killer'

On a snowy December night in 1981, DiGiulio drove Sullivan in a peach-colored Cadillac to the Blue Gardenia, a restaurant on Empire Boulevard that was popular with the mob associates who lived on the east side. The pair waited in the parking lot for just a few minutes before Fiorino pulled in in his Lincoln Continental.

"That's him," DiGiulio told Sullivan. Sullivan stepped out of the car and shot Fiorino in the head with a shotgun.

Only blocks away, an Irondequoit policeman, Michael DiGiovanni, was on patrol. He'd only been on the force three years and had not yet heard of the nearby homicide when he saw the Cadillac speed out of the restaurant's parking lot.

He pulled behind the car, which ran a red light and then began swerving. DiGiullio lost control of the car, and it came to rest off the road.

DiGiovanni, now a lieutenant with the Irondequoit police, says he thought he'd witnessed a drunk driving accident, but that changed when the driver jumped from the car and ran. The moments that followed are still fresh in his mind today. He remembers making eye contact with Sullivan as he emerged from the passenger door with a long gun in his hands.

"I kicked open my car door and as I came out he was firing at me," he said. "I counted three [shots]."

As the blasts shattered the windshield of his patrol car, DiGiovanni said he fired two or three quick shots from his own revolver before moving to close the distance between him and Sullivan.

"I popped the rest of the rounds out and I saw him lurch forward so I knew I hit him," DiGiovanni said. "I went down, reloaded my gun, came back up, and he was gone."

Once other police and sheriff deputies arrived, they tracked DiGiulio by the footprints he'd left in the snow. The tracks led to a school on Helendale Road. "We caught him in the bushes," DiGiovanni said.

Sullivan had disappeared into the night, but DiGiovanni's traffic stop helped provide clues to the Fiorino murder and other crimes. In the trunk were the proceeds of a bank robbery in Utica and evidence which later linked Sullivan to a homicide on Long Island.

DiGiovanni knows it was almost happenstance that he crossed paths with Sullivan that night. If he'd lingered a few minutes longer at dinner, or if the getaway driver had turned right rather than left, Sullivan might have escaped without police ever knowing he'd been in town.

Once in custody, DiGiulio told police of the hit man who'd been hired to murder Fiorino. Sullivan's reputation was well-known to the FBI and others in law enforcement.

"He was believed to be a stone-cold contract killer," Dillon said.

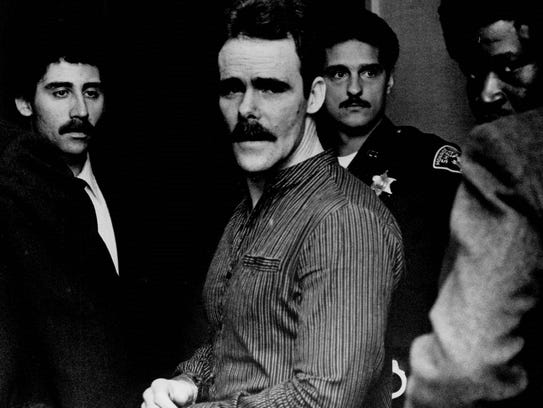

Two months after the homicide, police received a tip: Sullivan was back in Rochester, and he was looking for remaining payment for the killing.

Hugh Higgins, who had headed the FBI Office in Rochester and had moved to Eastman Kodak Co.'s security office, received the call, Dillon said.

Higgins "answered the phone and had an anonymous male caller say Sullivan was in 'such-and-such a room' at the (Denonville Inn) motel" in Penfield.

"We got somebody out there right way and we were able to establish the car in front of that particular room was from King's County," Dillon said. Agents staked out the room and arrested Sullivan as he was loading suitcases into the car.

Sullivan was later convicted of the Fiorino murder and two others. He was in Fishkill Correctional Facility in Dutchess County when he died Friday. He was not scheduled to be paroled until 2061, when he would have been 122 years old.

"He was remorseful," said Manhattan-based author T.J. English, who interviewed Sullivan several times in prison and who wrote the definitive history of the Irish organized crime, The Westies: Inside New York's Irish Mob. "He knew that the things he had done were wrong. He knew he was going to be in prison for the rest of his life, and rightfully so."

Joseph John Sullivan

Escape from Attica

Sullivan's father was a decorated New York City police detective, who died when Sullivan was 11 years old. With a domineering mother who struggled with the loss of her husband, Sullivan fell into criminal circles. He amassed a laundry list of crimes — from petit larcenies to armed robberies — before reaching adulthood.

In 1967 he was convicted of second-degree manslaughter for the killing of a father of eight children in a Queens tavern. Four years later, he pulled off his escape from Attica.

Sullivan managed to bury himself beneath a pile of empty flour bags that were in the back of a truck leaving the prison. He was found six weeks later in Greenwich Village and returned to prison. He was paroled in 1975.

Over the next seven years, Sullivan built his reputation as a contract killer.

"His feeling was that somewhere early in life he became a professional gangster and a professional killer," English said. "He took a certain pride in his work. He was expected to do it in a certain manner that it wouldn’t be traced back to anybody.

"He was an old-school tough guy. He had a gravelly voice. He sounded like something out of an old Jimmy Cagney movie."

Sullivan was known for a vigorous workout regimen with hundreds of push-ups daily that kept him fit in prison. But he was stricken with a cancer that required the removal of a lung, English said.

Sullivan and his family have been featured in television documentaries. His wife, Gail Sullivan, has promoted a book she and her husband wrote, Tears and Tiers: The Life and Times of Joseph "Mad Dog" Sullivan.

The couple has two adult sons.

"Sullivan was able to create some semblance of a normal life the 30 years he was in prison," English said. The sons "turned out to be terrific kids."

"I thought there was something almost heroic about it, the way he was able to create a nuclear family, a decent family."

http://www.democratandchronicle.com/story/news/2017/06/15/joseph-mad-dog-sullivan-dies-rochester-mob-hit/399721001/

0 comments:

Post a Comment