Wall Street trader and NFL players targeted in $4M scheme tied to Colombo family

In early 2007, a Wall Street trader waltzed inside a West Palm Beach, Fla., factory to see a futuristic product pitched as his fast track to making a faster mint.

Visitor Mark Spanakos surveyed a bustling operation with a professional-looking staff clad in pristine white lab coats, protective goggles and hardhats.

Here, as his host on the 15-minute tour explained, production was underway on a newly patented, high-tech, highly profitable fingerprint identification device.

The impressed Staten Islander couldn’t know what he alleges is the truth: There was no production, no product, no patent.

He soon learned about the lies.

Spanakos’ fibbing best friend had lured him into a scam. He would lose a $4 million investment in the sham company, Hawk Biometrics — described in court papers as a mobbed-up farce, a racketeering enterprise intent on fleecing its investors.

One of its principals, a reputed made member of the Colombo crime family, even threatened to whack Spanakos during a 2013 deposition.

“You are a f---ing dead man!” he reportedly screamed in front of a roomful of witnesses.

More than a decade after touring the fake Florida factory and despite his repeated pleas to law enforcement about Hawk, the duped Spanakos is still fighting in court and hoping for justice — if not compensation.

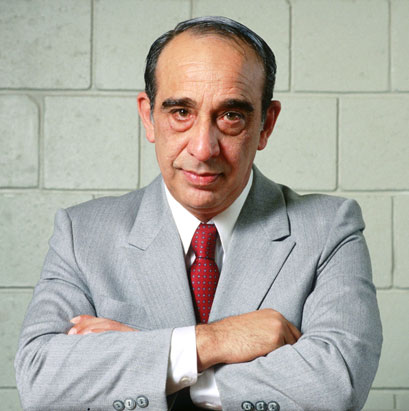

David Coriaty is accused of running an investment scheme with Hawk Biometrics.

He’s not alone: The alleged scam duped investors in 13 states, along with an additional 14 New York commodities dealers, several NFL players and an assortment of hardworking mom-and-pop types.

Their investments disappeared in a rip-off rife with “fraudulent financial reports, self-dealing, engaging in insider trading, manipulating stock prices and acting in material detriment of the company and its shareholders,” according to court papers.

Spanakos’ allegations were once deemed credible by a Palm Beach police detective, and he even carried a briefcase fitted with a recording device as the FBI investigated the case.

Yet somewhat inexplicably, no one was ever indicted, arrested or prosecuted. Why?

“That’s exactly the question everybody is asking: Where is the Securities and Exchange Commission, the FBI, the IRS?” said attorney Cathy Lerman, who represents a dozen of the victims.

“There’s something really, really wrong here. These guys were blatant and fearless.”

One-time Hawk director David Coriaty said the various probes only prove the operation was legitimate.

“Every law enforcement agency investigated this and not only cleared us but asked Spanakos why he went to them in the first place,” he said.

Promotional materials by the phony mob-tied firm, Hawk Biometrics.

Incredibly, the allegedly crooked company is still operating — and trading on the NASDAQ. On Feb. 2, though worth less than a penny apiece, 105,000 Hawks shares moved.

Spanakos, now 58, was known as “Shark” on the floor of the New York Mercantile Exchange, where he befriended colleague Edward "Seby"Sebastiano.

“We were best friends, joined at the hip,” he recalled. “We rode motorcycles. We hung out with a lot of guys who worked together. It was a great life.”

And so when Sebastiano approached Spanakos with an offer to get an early piece of a new personal identification product, he listened.

And then Spanakos invested.

“It sounded like a great idea, especially after 9/11,” Spanakos recalled. “The device would read the constellation of blood vessels in your finger. You would need a match to start your car, open the door to your car, for ATMs and banking and credit cards.”

“The Power of Touch” became one of Hawk’s promotional tag lines. Spanakos became a true believer, investing his own cash — and even persuading his clerk to invest $100,000.

His former Wall Street worker now drives a cab.

Pittsburgh Steelers defensive back Bryant McFadden sits on the bench in the second half of an NFL football game against the Baltimore Ravens in Baltimore, Sunday, Sept. 11, 2011.

The powers behind Hawk, as identified in court papers and by Spanakos, included a scary coalition of opportunists, gangsters and thieves.

One hailed from New York City: Robert Pate, a former Colombo family soldier and Sebastiano’s brother-in-law.

His brother John Pate, identified by the FBI as a mob capo, reunited with Robert in Florida after finishing a 10-year federal prison stint in October 2003.

John Pate, was a made man, a combatant in the early 1990s Colombo family war that left a dozen people dead. He was also charged with the 1985 murder of boss Carmine Persico’s son-in-law, who was left to decompose in a car trunk outside Nathan’s in Coney Island.

Hawk operated under the guidance of the muscular, tattooed David Coriaty, who boasted of a nonexistent college football career at the powerhouse University of Miami and a short, bogus pro stint with the Dolphins.

Like Robert Pate, he came with a brother: Ehab Coriaty, who was convicted in 1999 of one count of conspiracy and eight counts of wire fraud for bilking his boss of roughly $1 million in investment funds.

David Coriaty “seemed to be a cool guy,” recalled ex-NFL defensive back Bryant McFadden, an early Hawk investor. “I thought he was straightforward. . . . He seemed legit.”

No surprise there. The Hawk crew put together a flashy sales come-on for potential investors.

Lynda and Larry Pennington were among the investors who were lured into the scam in Florida.

“Hawk Biometrics patents are unmatched in the industry to deliver ultimate state-of-the-art security technology,” the company boasted.

Among its claims: Prospective clients included several major car companies and Donald Trump’s Palm Beach resort Mar-a-Lago.

Except there were no deals or orders for the product. And the company misspelled the name of the exclusive oceanfront property as one jumbled word: Maralago.

Spanakos soon smelled something fishy on the Florida coastline.

Investment money was spent by David Coriaty on a highflying lifestyle involving private planes, expensive jewelry, luxury automobiles and Las Vegas gambling junkets, according to court documents.

McFadden, now 36, recalls Coriaty showing him a “prototype” of the device, installed in the executive’s silver Lamborghini.

The athlete invested $100,000, and later doubled down with a $100,000 loan. The longtime Pittsburgh Steeler, a second-round draft choice in 2005, lost every penny.

According to Spanakos’ still-pending 2010 lawsuit, the company reported $22 million in expenses against a mere $5,570 in sales between October 2007 and September 2010.

David Coriaty, one-time Hawk director, allegedly gave investors tours of the Florida factory in West Palm Beach where Hawk Biometrics prototypes were supposedly being produced.

The broker wasn’t alone in his suspicions.

The NFL Players Association warned its members in a 2010 memo to steer clear of Hawk, encouraging any player with money already invested to hire an independent auditor.

That unfortunate group included star wide receiver Anquan Boldin, along with fellow Florida State alums McFadden, Greg Jones and Alex Barron.

The Spanakos lawsuit was filed the same year.

“That raised my eyebrows a little bit,” said McFadden. “Coriaty downplayed it, said that was a lie. He got a bit salty, and said Spanakos was trying to take down the whole thing.

“And he said he would meet with me. And of course, that never happened.”

Hawk allegedly used the victimized athletes’ names as a lure for other unfortunate investors. The company’s 2008 “Management and Advisory Team” featured a picture of Boldin — without his permission.

In a February 2013 deposition, Boldin testified about losing $250,000 to Hawk. The company did cut a $10,000 check donated to Boldin’s charity foundation, apparently at the direction of Coriaty.

Robert "Bobby" Pate, Colombo mobster.

“I think it was (at his request),” said Boldin. “But I think the check bounced.”

In the same year as the NFL memo, Spanakos — a former member of the Hawk board of directors — filed his lawsuit against the company, laying out the entire pump-and-dump operation.

The legal fight has now lasted longer than McFadden’s seven-year NFL career.

David Coriaty was described as the de facto CEO/chairman, and Spanakos’ old pal Sebastiano as a fellow board member.

“Spanakos eventually learned that Hawk did not own patents, nor did it own pending patents and trademarks in biometric technologies,” his lawsuit charged. “The board’s statements to investors were false.”

The top executives were nonetheless collecting high six-figure salaries and cash payments for “consulting” duties, while providing interest-free loans to the scammers and their families, the lawsuit alleged.

Phony documents were supposedly filed with the Securities and Exchange Commission.

David Coriaty’s annual compensation was listed at $800,000. Court papers charge that $25,000 in company money paid for his second wedding, and an additional $50,000 was funneled to his ex-wife — along with 500,000 free shares of Hawk stock.

This Hawk Biometrics fingerprint sensor installed onto a car dashboard.

A subpoena filed by Spanakos’ lawyer for Hawk bank records indicated another $7.5 million was embezzled by the board of directors for personal use.

And board members approved the sale of 100 million shares of new stock at “penny stock” prices, crushing earlier investors who watched as their $3 shares plummeted to one thin dime per share, according to court papers.

Insiders buying at the new low price then turned profits as the company, touting the involvement of the NFL players and hyping the business’ prospects, allegedly brought in new investors to fleece and watched the stock value rise.

None of it seemed possible when Spanakos visited the factory. He remembers taking in a grand illusion perpetrated by the men at the center of the fraud.

“Very impressive — definitely impressive,” he recalled of the factory. “Absolutely. And anybody we brought there felt the same reassurance: They’re doing what they said they’re doing. Testing and retesting.”

Coriaty charges that Spanakos, rather than a victim, is the cause of Hawk’s demise — and he’s perplexed as to why.

“I cannot explain Spanakos’ motivation except to suggest that he is a bad person,” said Coriaty. “He caused every single person to lose their money — in some cases their life savings — out of greed and acting like a scolded child. . . . This guy is a horrible human being.”

Spanakos continues to pursue the case simply because he can, added Coriaty.

Spanakos picked up hints something was wrong with the company after Hawk Biometrics lied about its product and messy promotional schemes.

“He had and has more money than the rest of us and that robbed us of our ability to fight him,” he said.

Among the other visitors convinced by the plant tour were Larry and Lynda Pennington, who were steered around the factory by Coriaty himself.

The senior citizens were lured into the scam by a work colleague of Larry, with whispers of an insider’s shot at turning a tidy profit to boost their retirement fund.

The pitch, like ripples in a pond, soon reached relatives and neighbors.

“Other friends and family became investors,” said Larry, 71. “They brought them in as they needed more suckers.”

The couple wound up losing more than $80,000 in retirement funds, and are selling their Florida house with its two-car garage for an 825-square foot apartment in Pittsburgh.

“It still makes me want to sock (Coriaty) in the face,” said Lynda, 68. “He’s a silver-tongued devil. Not a true word comes out of David’s mouth. . . . I worked hard for that money.”

Coriaty disputes the allegations brought by the Penningtons and other investors.

Florida State running back Greg Jones celebrates a touchdown in the second quarter against Virginia, Saturday, Aug. 31, 2002, in Tallahassee, Fla.

“McFadden never called it a scam and the Penningtons got half their money back,” said Coriaty.

Spanakos eventually became so frustrated that he marched uninvited into the FBI’s West Palm Beach office in March 2009 to share his remarkable tale.

“Just walked in blind,” he recounted. “They asked me to sit down, like on television, and started the interrogation. They start pushing mug shots in front of me — ‘Do you know this guy? This guy’s a made guy.’

“I’m thinking they’re killers maybe. That really shocked me, who the FBI said they were.”

He agreed to bring a wired-up briefcase to a meeting with Coriaty, Sebastiano and a third man, recording a two-hour conversation about the whole mess.

A few months later, the FBI ended its investigation without explanation.

In November 2012, Spanakos visited with a detective in the Palm Beach County sheriff’s office, where he found a sympathetic ear.

“A preliminary review confirmed Spanakos’ allegations as well as the alleged organized scheme to defraud investors and the public,” read a Jan. 3, 2013, report. “This case is now open and further investigation continues.”

Anquan Boldin #4 of the Florida State University Seminoles watches the ACC game against the University of Maryland Terrapins on Sept. 14, 2002.

And it did. Until it didn’t again.

The Palm Beach investigator contacted the FBI in February 2016 after receiving a subpoena about the allegations brought by Spanakos.

“I contacted FBI special agent (redacted) to determine the status of this case,” the investigator wrote in a March 1, 2016, report.

“It was determined that the FBI declined to prosecute this case and that no further investigation would ensue.”

Spanakos was stunned, recalling a conversation in which the Palm Beach detective called the case a slam dunk with arrests likely in two weeks.

A Freedom of Information Act request for documents on the case, filed with the FBI last June, has yet to produce a response. An agency spokesman did not return an email for comment.

The SEC declined to comment on the case, and the Palm Beach investigator ignored emails about his probe.

Spanakos was even more stunned by an outburst following the Dec. 3, 2013, deposition of Robert Pate’s daughter regarding allegations of money-laundering. As she answered questions, Pate stared directly at Spanakos and dragged one hand across his abdomen as if gutting a fish.

“You are a f---ing dead man, Spanakos!” screamed Pate when the Q&A concluded. “You’re f---ing dead!”

McFadden spoke to Coriaty for the final time about four years ago, when he heard the same old phony song and dance.

“The last thing I heard was he wanted to meet with me and send some documents to show everything was legit,” said McFadden. “Same pitch as before.”

Larry Pennington, like Spanakos and McFadden, holds out hope for a resolution of the long-pending case. But his optimism, despite what he sees as the obvious nature of the scam, wanes with each passing year.

“If somebody came up and robbed you with a gun, they go to prison for 25 years,” said Pennington.

“But they sit there and they do this, and they’re untouchable.”

http://www.nydailynews.com/news/crime/wall-street-trader-nfl-players-hit-hard-4m-mob-tied-scheme-article-1.3813029

0 comments:

Post a Comment